Patterns of scaling impact

This article is not based on rigorous research, but an observation of patterns I have seen over my 7 years of working with mission driven entrepreneurs. I will reflect on what I perceive patterns of generating impact are and where limitations to scaling these might lie.

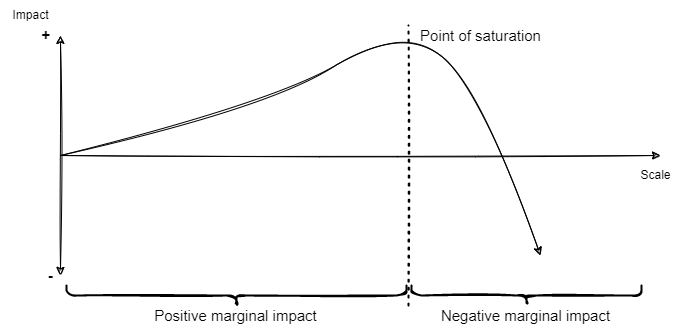

The classic pattern of industrialisation

When speaking of industrialisation I’m referring to methods of production that increase productivity, offer a degree of standardisation, exploit resources and in most cases produce greenhouse gas emissions. Although often portrayed as the root of all evil, industrialisation within limits has its benefits. Think for example intensive agriculture: For all its faults it has dramatically improved crop yields, enhanced food security and improved human wellbeing. Only after a certain scale of intensive agriculture do we experience its detrimental effects, when taken to levels of deforestation, mono cropping and so on (long list…).

The pattern of impact here is thus, that industrialisation will initially bring improved utility. As the scale increases the net impact of the utility will be diminished by adverse effects of production, up to a point of over-production. Beyond this point we are over-consuming the produced good with no additional benefit, but all the adverse effects of production and added adverse effects of over-consumption.

Going back to the food example this point is reached where food is wasted, over-consumption leads to obesity and our scale of intensive agriculture harms the planet.

The offsetting pattern

Offsetting in a nutshell is where one activity with positive environmental impacts is promoted to make up for another activity’s negative environmental impact. This approach is debatable, but considering that there might be positive effects on human wellbeing for example from industrialisation, offsetting can be useful to reduce the negative environmental effects from it. The challenge with offsetting comes from the fact that activities which initially have a positive environmental impacts can become harmful when done too much.

A perfect example of this is planting trees for carbon sequestration. Each tree planted will capture CO2 while it grows, providing a positive marginal impact by reducing atmospheric CO2. Trees however require resources themselves such as soil nutrients and water. Therefore when too many trees are planted in an area or the wrong species of tree is planted they will adversely impact the surrounding ecosystem. We have seen eucalyptus being planted in South Africa to serve offsetting demand. This has led to the trees drying out the surrounding grass lands, destroying biodiversity, increasing risk of wild fires and ultimately realising more CO2 into the atmosphere than they capture. In this example the scale of activity did not just result in negative marginal impact, but led to a net negative overall impact.

Therefore offsetting activities cannot be scaled indefinitely and no single activity should be considered a silver bullet.

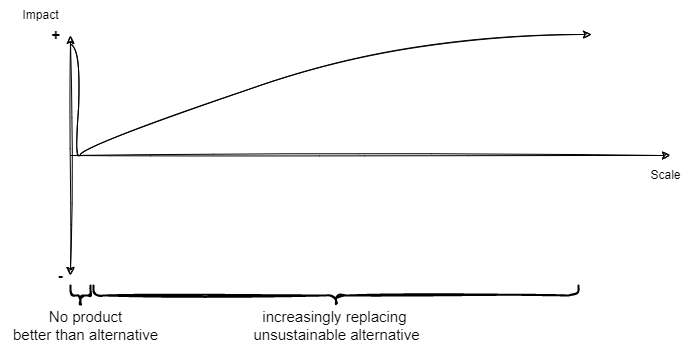

The pattern of environmentally friendly substitutes

A common activity in ecopreneurship is developing an environmentally friendly substitute to an existing product. Bringing this to the market can then replace the original product with its environmentally adverse impacts. Think the electric car, the biodegradable plastic or the paper straw.

What’s important to note in this example, that the highest impact will stem from not producing and consuming the product at all. The straw you never used will always have a lower footprint than even the most environmentally friendly one that still requires some resource to produce. Every car that is not made is always better than even an electric one. Yet some products are needed and simply not having them is not an option (for whatever reason). In this scenario the positive impact will grow with each product replaced. Eventually the marginal impact will decrease until a point is reached where no more of the unsustainable old product exists. When we continue producing the new sustainable alternative beyond this point, our graph will go back to looking like the first one and over consumption will bring adverse effects unless by some miracle we have products that require no resources and energy, and that create no waste.

With these in mind, it is important to consider what products we are bringing into the market place and to be mindful of the limitations to scale that exist for them. Infinite growth on a finite planet seems to remain a mare for the foreseeable future.